A Naprendszernek is van mágneses védőpajzsa, a HELIOSZFÉRA. Védő Pajzsot fel!

Ha láttál már egy Star Trek filmet, akkor tudod, milyen fontos a pajzs. Mikor egy csillag felrobban, vagy ha éppen egy Klingon hadihajó zöld sugárnyalábja világítja be azűr vákuumát, akkor a kapitány parancsa két szóból áll: "Pajzsot fel", és minden rendben.

Elhárító pajzs: ne menj el otthonról nélküle.

Hiszed vagy nem, a Naprendszernek is van egy.

A Helioszféra egy művészi elképzelés szerint | A Naprendszer elhárító pajzsa egy óriási mágneses gömb, melynek neve Helioszféra. Ez része a Nap mágneses terének. Senki sem tudja precízen megmondani a Helioszféra méretét. Az biztos, hogy határa túl van a Plútó pályáján, így mind a kilenc bolygó élvezi a védelmét.

A Helioszféra fontos a földi élet számára. Néhány millió évvel ezelőtt például egy csillaghalmaz haladt el a Tejútrendszer hozzánk közel eső részén. A csillagok életük befejeztével szupernóvaként sorra felrobbantak, mint a pattogatott kukorica. A robbanások által keltett kozmikus sugárzás nagy részét elhárította a Helioszféra, megmentve korai elődeinket a sugárfürdőtől.

Ez a buborék azonban messze nem tökéletes. A valóság az, hogy olyan mint a szita, mondja a New Hampshire-i egyetem csillagásza, Eberhard Moebius. Bizonyos dolgok átjutnak rajta. (A Star Trek-ben is ez történik. Ha a hajók pajzsa áthatolhatatlan lenne, soha nem látnánk a filmbenűrbéli harcjelenetet.)

Eberhard Moebius | Vegyük a kozmikus sugárzást. Ennek nagy része szupernóva robbanás által széttört és fénysebességre gyorsított atomokból áll. A Helioszféra ezek mintegy 90%-át eltéríti, csak a legerőteljesebb 10% tud behatolni a Naprendszer belsőbb vidékeire.

A Helioszféra még sebezhetőbb elektromos töltés nélküli részecskékkel szemben. A mágneses tér eltéríti a mozgó elektromos töltéseket, vagy elektromos töltéssel rendelkező részecskéket, de nem tud mit kezdeni a töltés nélküliekkel, mint például a molekulákkal, porral, semleges gázzal.

Semleges hélium atomok folyama, egyfajta "csillagközi szél", mondja Moebius, jelenleg is behatol a Naprendszerbe. A hélium a kígyótartó csillagkép felől jön, s mivel semleges, a Helioszféra semmit sem tud tenni, hogy megállítsa.

Ennek a folyamnak a tanulmányozása fontos, hogy többet tudjunk meg a Helioszféráról. Milyen nagy? Mennyire áthatolható? Továbbá információkat szerezhetünk a csillagközi térben található gázokról, mondja Moebius.

Az Ulysses szonda a Jupiternél, melynek gravitációját

felhasználva sikerült kikerülnie a bolygók keringési

síkjából, így képes megfigyelni a Nap északi, mind déli

pólusát. 1990-ben lőtték fel. | A hélium folyamot 30 évvel ezelőtt fedezték fel, jelenleg a NASA és az ESA több szondája is figyeli tulajdonságait: SOHO, EUVE, ACE és különösen az Ulysses nevű szonda. E szonda a folyamból mintát is tud venni, míg a többiek csupán közvetve vizsgálhatják. Például az EUVE, amely a folyam által szétszórt ultraibolya fény tanulmányozásából von le következtetéseket.

Sok éven át a hélium folyam tulajdonságairól a tudósok csak nagy bizonytalansággal, rengeteg "ha", "valószínű" szó használatával tudtak nyilatkozni. "Mostanra azonban, hála a modern szondák vizsgálatainak megváltozott a helyzet", mondja Moebius. Jelenlegő a vezetője Svájcban a Nemzetközi Űrtudományi Intézetnek. A szondák adatait felhasználva meg tudják mondani a folyam mindenkori hőmérsékletét, sűrűségét és sebességét.

A Helioszféra. Forrás: A Nap és bolygói | A folyam hőmérséklete 6000 fok körüli, hasonlóan a Nap felszíni hőmérsékletéhez. Az űrszondák "átszállva" a folyamon persze nem olvadnak meg, de még nem is melegednek fel tőle. A folyam ugyanis rendkívül ritka, magyarázza Moebius. "Csak 0.015 hélium atom található köbcentiméterenként a folyamban." Összehasonlításképp: a Föld légköre tengerszinten ezer milliárdszor-milliárdszor (10^21) sűrűbb, a napszél sűrűsége a Föld közelében pedig 5-10 részecske köbcentiméterenként. A folyam sebessége 26 km/s körül van, azaz 93 600 kilométert tesz meg óránként.

E számok megerősítették a csillagászokat abban, amit már régóta sejtettek. A Naprendszer összeütközik egy hatalmas csillagközi felhővel.

A legtöbb ember az gondolja, hogy azűr üres. Valójában nem. A csillagok közti "hézagokat" gázfelhők töltik ki. A felhők a Földön kilométer szélesek, a felhők azűrben fényév szélesek. Jellegüket tekintve vannak hideg, tinta-fekete felhőktől kezdve egészen színes, forró, mondhatni izzó felhők is. Minden csillag egy felhőből keletkezi egyszer, s halálakor is egy felhőt hoz létre, többet pedig mozgásra kényszerít.

A kérdés az, milyen ez a felhő?

A helyi felhő | A felhő, hasonlóan az Univerzumot felépítő legtöbb égitesthez, leginkább hidrogénből áll. A hidrogént magát jól ismerjük. Tudjuk, hogy a csillagok fényéből milyen hullámhosszú fényt nyel el (abszorbál), majd szór szét, így a környező csillagok fényében a hidrogén jellegzetes vonalait figyelve feltérképezhetjük a felhőt: néhány fényév széles és egy felhőhöz híven eléggé szabálytalan.

A felhő gazdag hidrogéntartalma nem tud egykönnyen behatolni a Helioszférába, mert a hidrogén nagy része a felhőben ionizáltan van jelen a csillagfény ultraviola tartalma végett. A kozmikus sugárzáshoz hasonlóan e hidrogén is elektromos töltéssel rendelkezik, ezért szinte "lepattan" a buborékról. A felhőben található hélium atomok azonban gond nélkül behatolnak a Naprendszerbe, mivel ezeket a csillagok fénye nem ionizálja.

Ámbár a hélium igen kis részarányban alkotja csak a felhőt, a kutatóknak mégis elárulja, milyen is lehet az. A hélium folyam hőmérséklete 6000 fok, a felhőnek is annyinak kell lennie. A folyam sebessége 26 km/s, a felhőnek szintén. Ha a felhőben a hidrogén és a hélium aránya átlagosnak mondható - elfogadható feltételezés -, akkor a felhő átlagos sűrűségének 0.264 atomnak kell lennie köbcentiméterenként.

A Helioszférába hatolt semleges gázt a Nap gravitációja eltéríti, mintegy fókuszálja.

A "Fókuszpontban" a gáz sűrűsége többszöröse lesz az átlagosnak, nagyban segítve

a szondák vizsgálódását. A gáz a Nap gravitációja hatására a térben kúp formába rendeződik. | Ezek a számok fontosak. Meghatározzák a Helioszféra méretét, áteresztő képességét, azaz az általa nyújtott védelem erősségét. A buborék felfújódni próbál a napszél kifelé irányuló nyomása végett, míg összehúzódni a felhő hatása miatt. Ha a felhő nyomása nagy, (ez a felhő hőmérsékletétől, sűrűségétől, sebességétől függ), akkor a napszél hatását hamar elnyomja a felhő, csökken a buborék mérete, csökken védelmünk a kozmikus sugárzás ellen.

Néhány kutató úgy gondolja, hogy sok ezer év múlva a Naprendszer teljes egészében átszeli a felhőt, kiérve belőle egy alacsony sűrűségű üregbe ér, amit azok a néhány millió évvel ezelőtt felrobbant szupernóvák alakítottak ki. A Helioszféra ki fog tágulni, így a védelmünk is növekedni fog.

És utána mi lesz? Ki tudja! Valószínűleg egy újabb felhőbe fog a Naprendszer behatolni, így lecsökken majd a buborék mérete, mind a védelem foka.

Összefoglalva: a Naprendszer jelenleg egy csillagközi felhőn halad át, amelybe a Helioszféra mintegy lyukat fúr, melytől gömb formája elnyúlt csepp alakká torzul. Mivel a felhő túlnyomórészt ionizált hidrogénből áll, nem jut be a Helioszférába, hanem azt kikerülni igyekszik. A felhő héliumtartalma és egyéb elektromosan semleges alkotórészei viszont szinte akadálytalanul behatolnak a Helioszférába. Ezt nevezik hélium folyamnak. A kozmikus sugárzás elleni védelem függ a Helioszféra méretétől, amit egyrészt befolyásol a csillagközi felhő sűrűsége, sebessége, hőmérséklete, másrészt pedig maga a Nap, a naptevékenység. Szoláris maximumkor, mikor a napszél sebessége nagyobb, és sűrűbb is, nyilván nagyobbra tudja fújni a Helioszférát, mint minimumkor.

Pajzsot fel? Pajzsot le? Ez már nem sci-fi mostantól.

Ezen írás készült a Science@NASA oldalán megjelent cikk alapján. Üdvözlettel Polgár Sándor

The Flow of Interstellar Helium in the Solar System

20 Sep 2004

'Consensus on conditions in the cloud of interstellar gas surrounding the Sun from several in-situ observation methods'

Through coordinated observations with instruments on several ESA and NASA spacecraft and a collaborative analysis effort hosted by the International Space Science Institute (ISSI) an international team of scientists has compiled for the first time a consistent set of the physical parameters of helium in the very local interstellar gas cloud the surrounds the solar system.

Careful analysis of data from three complementary observation methods produced a reliable set of physical parameters for the local cloud which can be used to model the interaction between the Sun and the surrounding interstellar gas and establish dimensions of the solar system.

The three independent observational methods use:

- the direct analysis of interstellar neutral helium atoms that penetrates close to the Sun

- the production of ions from this gas and their transport with the solar wind

- and scattering of solar UV light from the penetrating gas, which, until recently, was the only method for estimating these parameters.

Knowledge of physical characteristics of extrasolar material, obtained with these local space measurements, represents an important step in our understanding the Sun's interaction with its immediate interstellar neighbourhood.

The Sun is located in the outskirts of the Milky Way, about 30 000 light years from its centre, embedded in a fairly dilute and warm cloud of interstellar gas, which consists of a mixture of neutral and ionized gas or plasma. This cloud material represents a sample of today's interstellar matter in our Milky Way Galaxy from which stars and planetary systems form. In the case of the Sun and its planets this occurred about 4.5 billion years ago. Differences in the composition of these two samples of galactic matter tell the story of the evolution of matter in the galaxy as heavy elements are added by dying stars.

The solar wind, which expands radially from the Sun at supersonic speed, blows a cavity - the heliosphere - into the surrounding interstellar cloud, filling it with solar material and magnetic field. The plasma component of the interstellar gas is kept outside the heliosphere.

By balancing the solar wind ram pressure, which is easily measured, against the pressure of the surrounding cloud, the size and shape of the heliosphere is determined. With the new consensus set of interstellar helium parameters, its density, temperature, flow direction and speed relative to the Sun, the interstellar pressure can now be computed more reliably and the roughly 100 AU size of the heliosphere more accurately determined.

Because the Sun's motion relative to the surrounding gas, an interstellar breeze of neutral atoms blows through the heliosphere, very much like the wind felt when driving an open car. Only very close to the Sun is the neutral gas ionized by the Sun's UV light and the by the solar wind, which leads to a small cavity in the neutral gas, roughly of several AU in size. Except for hydrogen, which is affected by radiation pressure, the Sun's gravity deflects the neutral gas flow, leading to a concentration of neutral gas density in the direction opposite to inflow direction of the gas.

|

|

Figure 1: Interstellar flow in the inner heliosphere, locations of observations, and inserts depicting the observations. |

The resulting flow pattern is shown in Figure 1 for helium. It is this flow pattern that is analyzed to derive the flow speed, its direction, and temperature. Helium, the second most abundant element after hydrogen, distinguishes itself by infiltrating closest to the Sun, to distances even inside the Earth's orbit. Furthermore, because its density, temperature, and speed are not affected by processes at the heliospheric boundary, analysis of the properties of the helium gas inside the heliosphere allows one to establish the state of the pristine interstellar medium.

Since the late 1990's various instruments on a fleet of spacecraft have provided observations of interstellar helium. These observations are depicted schematically in Figure 1:

- The GAS instrument on the ESA/NASA Ulysses spacecraft collects images of the He gas flow (coloured insert), whose observed deflection by the Sun's gravity is translated into the flow conditions outside the heliosphere.

- NASA's EUVE has repeatedly scanned the focusing cone in the light of the He line at 58.4 nm as illuminated by the Sun (yellow insert).

- The SWICS instrument on NASA's ACE spacecraft and on Ulysses collects He ions that are created inside the spacecraft orbit from the interstellar gas and then transported outward with the solar wind. The blue insert shows the pickup ion flux as the Earth passed the He cone in December 2000.

- UVCS on the ESA/NASA SOHO spacecraft observes the cone intensity at 0.2 - 0.5 AU in the He 58.4 nm line, as the first coronagraph that ever observed the interstellar gas. The green insert shows how the cone intensity decreases from 1996 (solar activity minimum) to 2000 (solar maximum) as the ionization, monitored with the CELIAS SEM sensor on SOHO, increases.

|

|

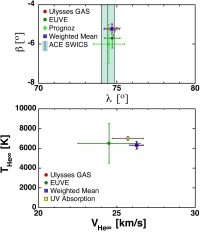

Figure 2: Flow direction in longitude and latitude as obtained by the different methods along with weighted mean (upper panel). Flow speed and temperature from the different methods and compared with astronomical observations (lower panel). |

Figure 2 shows a compilation of the observations along with weighted mean values from all available observations. The upper panel shows the flow direction, and the lower panel contains the flow speed and temperature. It is evident that the direct observation of the neutral atoms provides the flow characteristics with the least uncertainty.

A comparison with speed and temperature obtained through absorption of star light averaged over several light years indicates that these values appear to be typical for the entire cloud, for which other observations show that the Sun is located close to its edge.

The He density has been established to be 0.0151±0.015 cm-3 (Ulysses SWICS), 0.015±0.03 cm-3 (Ulysses GAS), 0.013±0.03 cm-3 (EUVE), with the pickup ions providing the smallest uncertainty.

Together with the recent observations by Voyager 1, indicating that this pioneering spacecraft is close to the termination shock or may have even crossed it temporarily (the termination shock is the boundary where the solar wind is quickly decelerated to subsonic speed) this consistent and accurate set of parameters is now beginning to provide strong constraints on models that describe the size and structure of the heliosphere.

A new team hosted by ISSI has started to extend this effort to hydrogen, a more complex task because about half of the hydrogen atoms do not penetrate the outer boundary of our solar system, which strongly affects their flow.

Science Team hosted by the International Space Science Institute (ISSI) in Bern

E. Möbius (Lead),1 M. Bzowski,2 S. Chalov,3 H.-J. Fahr,4 G. Gloeckler,5,6 V. Izmodenov,7 R. Kallenbach,8 R. Lallement,9 D. McMullin,10 H. Noda,11 M. Oka,12 A. Pauluhn,8 J. Raymond,13 D. Ruciñski,2,* T. Terasawa,12 W. Thompson,15 J. Vallerga,16 R. von Steiger,8 M. Witte17

(1) Dept. of Physics and Space Science Center, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH 03824, U.S.A.

(2) Space Research Centre, Warsaw, Poland

(3) Institute for Problems in Mechanics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia

(4) Institut für extraterrestrische Forschung, Universität Bonn, Bonn, Germany

(5) Dept. of Physics and IPST, University of Maryland, College Park, MD

(6) Dept. of Atmospheric, Oceanic and Space Sciences, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI

(7) Department of Mechanics and Mathematics, Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia

(8) International Space Science Institute (ISSI), Bern, Switzerland

(9) Service d'Aéronomie du CRNS, Verrières-le-Buisson, France

(10) Praxis, Inc., Alexandria, VA Space Science Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA

(11) National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, Misuzawa, Japan

(12) University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

(13) Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, MA

(14) Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD

(15) Space Sciences Laboratory, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA

(16) Max-Planck-Institut für Aeronomie, Katlenburg-Lindau, Germany

(*) deceased

Authors: Eberhard Möbius, George Goeckler and Rosine Lallement

Related articles

The complete results of the team meetings held at the ISSI will be presented in a series of 7 articles in an upcoming issue of the Astronomy & Astrophysics journal. The articles are:

Synopsis of the interstellar He parameters from combined neutral gas, pickup ion and UV scattering observations and related consequences, by E. Möbius, M. Bzowski, S. Chalov, H.-J. Fahr, G. Gloeckler, V. Izmodenov, R. Kallenbach, R. Lallement, D. McMullin, H. Noda, M. Oka, A. Pauluhn, J. Raymond, D. Rucinski, R. Skoug, T. Terasawa, W. Thompson, J. Vallerga, R. von Steiger, and M. Witte.

Kinetic parameters of interstellar neutral Helium: Review of results obtained during one solar cycle with Ulysses GAS, by M. Witte

Observations of the Helium focusing cone with pickup ions, by G. Gloeckler, E. Möbius, J. Geiss, M. Bzowski, H. Noda, T. Terasawa, M. Oka, D. McMullin, S. Chalov, H. Fahr, D. Rucinski, R. von Steiger, A. Yamazaki, and T. Zurbuchen

EUVE observations of the Helium glow: Interstellar and solar parameters, by J. Vallerga, R. Lallement, J. Raymond, M. Lemoine, B. Flynn, F. Dalaudier, and D. McMullin

Solar cycle dependence of the Helium focusing cone from SOHO/UVCS observations, by R. Lallement, J. Raymond, J.-L. Bertaux, E. Quemarais, Y.-K. Ko, M. Uzzo, D. McMullin, and D. Rucinski

Modelling the interstellar-interplanetary Helium 58.4 nm resonance glow: Towards reconciliation with particle measurements, by R. Lallement, J.C. Raymond, J. Vallerga, M. Lemoine, F. Dalaudier, and J.L. Bertaux

Heliospheric conditions that affect the interstellar gas inside the Heliosphere, by D.R. McMullin, M. Bzowski, E. Möbius, A. Pauluhn, R. Skoug, W. T. Thompson, M. Witte, R. von Steiger, D. Rucinski, M. Banaszkiewicz and R. Lallement |